Updated 2025-10-25T14:07:01Z

Share: Facebook | Email | X | LinkedIn | Reddit | Bluesky | WhatsApp | Copy link

Lightning bolt icon: An icon designed in the shape of a lightning bolt, symbolizing speed and impact.

Impact Link

Save | Saved | Read in App

This article is made available exclusively to Business Insider subscribers. Become an Insider today and begin exploring our in-depth reporting. Already have an account? Simply log in.

As waves of employees gradually transition back to on-site work, many are discovering that the contemporary office—often bright, clean, and open—has its own challenges, including limited physical space and, in some unfortunate instances, the unexpected reappearance of pests such as bedbugs. Whereas modern workplaces tend to embrace an open-floor aesthetic filled with natural light and communal areas, earlier generations of office design were defined by small, enclosed cubicles and even more rigid environments. In past decades, entire rooms were dedicated to typing pools, where rows of typewriters clattered in unison as secretaries produced correspondence and documents by hand. By contrast, in 2025 nearly every worker operates from a sleek, portable laptop, connected wirelessly to cloud-based systems and real-time collaboration tools.

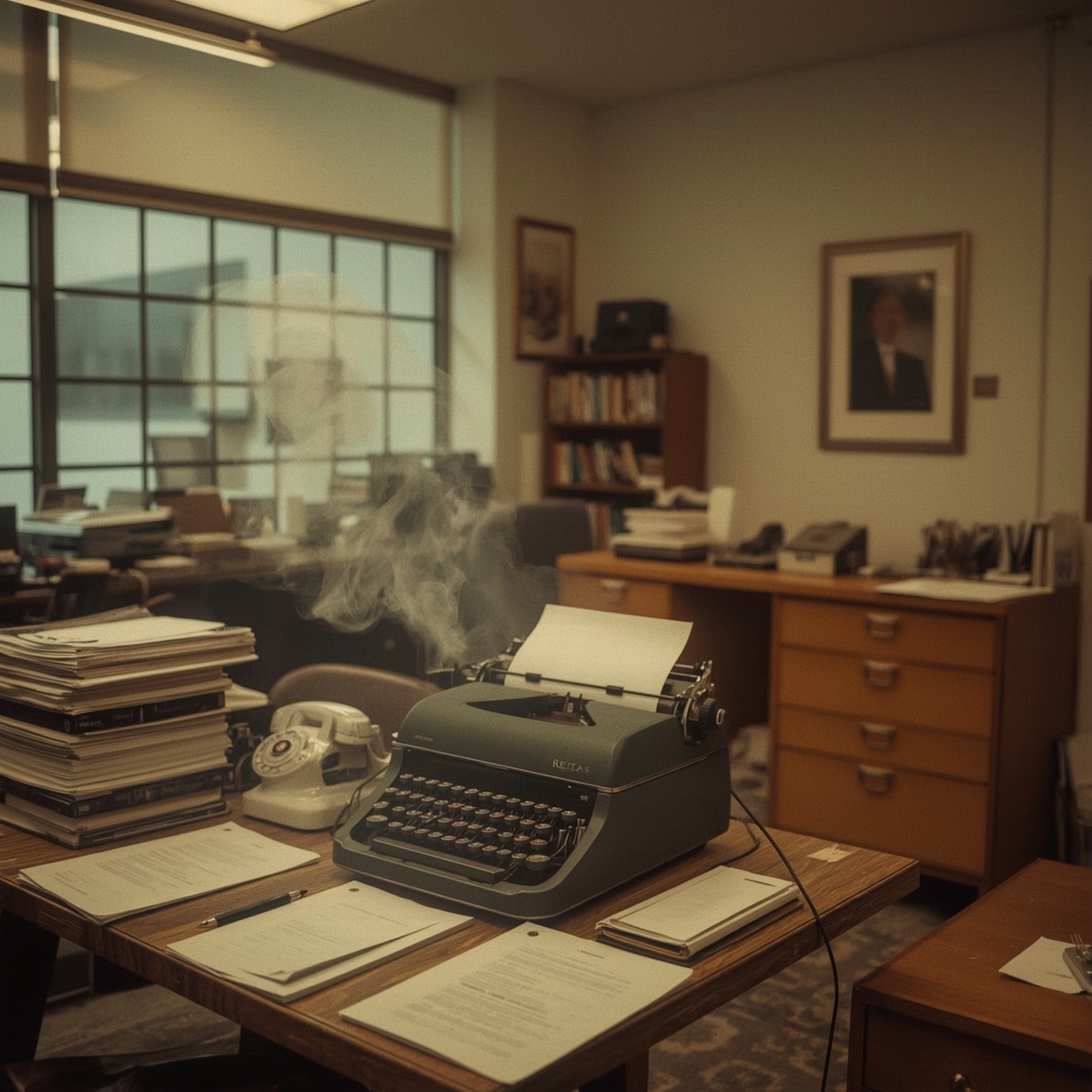

Cultural nostalgia, amplified by popular television shows like “Mad Men” and “Masters of Sex,” has reignited public fascination with office spaces from previous eras—periods portrayed as glamorous, industrious, and shrouded in a haze of cigarette smoke. Those dramatizations often remind modern audiences of a time before email, instant messaging, or virtual conferences—when communication relied on handwritten memos, switchboard operators, and, astonishingly, messengers speeding through corridors on roller skates to deliver notes across departments. Before digital devices replaced analog tools, the everyday rhythm of office life was dictated by the mechanical pulse of calculators, typewriters, and mountains of paper.

In the present day, massive corporate headquarters—such as Nvidia’s ultramodern complex in Santa Clara or Apple’s circular, glass-walled campus in Cupertino—emphasize open-air atriums, indoor gardens, and recreational amenities that rival resort facilities, including swimming pools and volleyball courts. This stands in stark contrast to many twentieth‑century workplaces, where employees might have considered themselves lucky simply to be seated near a window. Archival photographs capture this evolution vividly, revealing a progression not only in technology but also in attitudes toward space, ergonomics, and workplace safety. Browsing through these images allows us to appreciate how far corporate environments have advanced and invites reflection on what offices of the future might yet become.

One of the most striking differences between today’s offices and those of the 1940s is the omnipresence of cigarettes in the past. During that period, smoking was both socially acceptable and deeply ingrained in workplace culture. Gallup polling from 1944 reported that roughly 41% of American adults identified as smokers—a stark contrast to the approximately 11% documented by the CDC in 2022. Smoking was so common that it occurred almost everywhere: in grocery stores, restaurants, private homes, and indeed, in the office itself. Technically, federal law only prohibits smoking on airplanes and within federal buildings, leaving some states where indoor workplace smoking remains legal. Yet contemporary employers almost universally enforce bans, relegating smoking to designated outdoor areas. The image of American scientist Edward Wilber Berry calmly lighting his pipe at his workstation in the 1930s illustrates a bygone era. Although the traditional pipe faded from popularity by the 1990s, recent cultural trends suggest a modest revival among niche groups, as noted by The Times of London in 2024.

Before every workstation was dominated by a glowing monitor, desks offered broader physical space for tangible materials. A 1935 design office, for example, would have been scattered with drafting boards, slide rules, and geometric instruments—objects largely obsolete today. That busy workspace bears little resemblance to a modern design studio equipped with tablets, digital modeling software, and augmented reality displays. Even the meaning of “open plan” has transformed radically. Whereas a typing pool at Marks & Spencer’s headquarters in 1959 presented neat rows of typewriters manned by individual clerks, twenty-first‑century open offices feature expansive shared tables, ergonomic chairs, and collaborative zones designed to foster informal conversation and innovation.

Before the invention of electronic stock tickers, financial data dissemination was a slow, hands-on process. Employees manually printed out ticker tape, physically distributing updates across trading floors and to thousands of client terminals nationwide. In 1937, ticker information from the New York Stock Exchange reached about two thousand machines spread across 320 towns. The tape system’s last official iteration appeared in 1960, more than seventy years after Thomas Edison’s original design revolutionized finance. Though the machines have vanished, their linguistic legacy persists: the scrolling numbers on television financial news are still called stock tickers, and the concept even inspired the exuberant ticker‑tape parades of New York City—now re‑enacted with shredded paper instead of actual trading ribbons.

Communication has also been transformed beyond recognition. In 1960, secretaries often balanced multiple tasks—transcribing conversations while speaking on the phone—with the aid of early amplifying devices such as the Beoton telephone adapter. Today, those cumbersome tools have been replaced by apps capable of recording calls instantly and discreetly, while modern headphones and integrated speakerphones eliminate the need to broadcast private conversations across the office.

The typewriter, a definitive symbol of twentieth‑century clerical work, enjoyed a remarkably long reign. Invented in 1867, it reached mainstream popularity during the Industrial Revolution as record‑keeping and data management became integral to business operations. Photographs from 1937 depict entire rooms filled with workers testing typewriters before distribution. By the 1970s, offices had transitioned into hybrid zones where bookkeepers employed calculators and early computers alongside typewriters to manage vast ledgers of information. Notably, the profession remained and continues to remain dominated by women—Data USA’s 2022 figures confirm that 86.7% of bookkeepers in the United States were female, illustrating how some occupational demographics persist through eras of sweeping change.

The invention of the cubicle in 1968 by designer Robert Propst introduced a new concept aimed at improving focus and productivity by replacing the noisy open bullpen. Initially, the idea floundered; companies were slow to adopt the innovation until they realized it maximized space efficiency, enabling more employees to occupy a floor. By the 1980s and 1990s, cubicles had become ubiquitous, defining corporate aesthetics. Yet in the twenty‑first century, many organizations—including Shopify, Dropbox, and Business Insider itself—have returned to open layouts, citing collaboration as a central value. Interestingly, recent discussions have prompted a reevaluation of cubicles, suggesting that their resurgence might strike a healthier balance between privacy and community.

Before Slack channels or email threads existed, offices relied on swift-footed messengers to ferry urgent memos. A renowned New York cable company even equipped these employees with roller skates, boasting a 25% boost in delivery speed. However, such practices would now violate multiple safety codes, and computers have rendered physical message delivery unnecessary. Similarly, mid‑century workplaces often employed individuals known as “tea ladies,” whose role was to circulate with trays of refreshments, fostering brief moments of social connection amid the grind of paperwork.

Until the digital revolution, record‑keeping required meticulous maintenance of physical copies. Machines like the record‑card sorters of 1936 could process roughly eighty cards per minute, a marvel at the time though laughably sluggish compared to the instantaneous data synchronization of cloud systems today. Even phone booths—once emblems of communication privacy—seem quaint relics in an era of smartphones. Photographs from 1959 depict transparent booths that still exude a certain elegance despite their obsolescence.

The typical 1960s or ’70s desk, cluttered with rotary telephones, ashtrays, and hulking radios, stands in sharp contrast to the minimalist setups of the modern worker: thin laptops, wireless earbuds, perhaps a potted plant. Film critic Ian Christie’s 1968 office, preserved in an archival photo, offers a perfect visual time capsule. And though many vintage items—vinyl records, analog cameras, and typewriters—have recently enjoyed revivals among enthusiasts of tactile media, the broader shift toward digital tools continues uninterrupted. The abundance of ashtrays in those images subtly reminds us of how drastically workplace norms regarding health and professionalism have evolved.

It is difficult to fully convey just how thoroughly our work environments have changed in only a few decades. From the sound of clacking keys to the quiet hum of touch-sensitive devices, from enclosed cubicles to open collaboration hubs, the metamorphosis is massive. These transformations invite a larger, lingering question: if the past thirty years have brought such dramatic progress in design, culture, and technology, what unimaginable forms might our workplaces assume in the next ten, fifteen, or even thirty years?

Sourse: https://www.businessinsider.com/vintage-photos-offices-work-2018-10