2025-09-04T12:42:01Z

Share

Facebook

Email

X

LinkedIn

Reddit

Bluesky

WhatsApp

Copy link

lightning bolt icon

An icon in the shape of a lightning bolt.

Impact Link

Save

Saved

Read in app

This article is reserved exclusively for subscribers of Business Insider. Those who wish to access it in full are encouraged to become members and unlock the detailed narrative that follows. Existing members can, as always, log in to continue their reading experience.

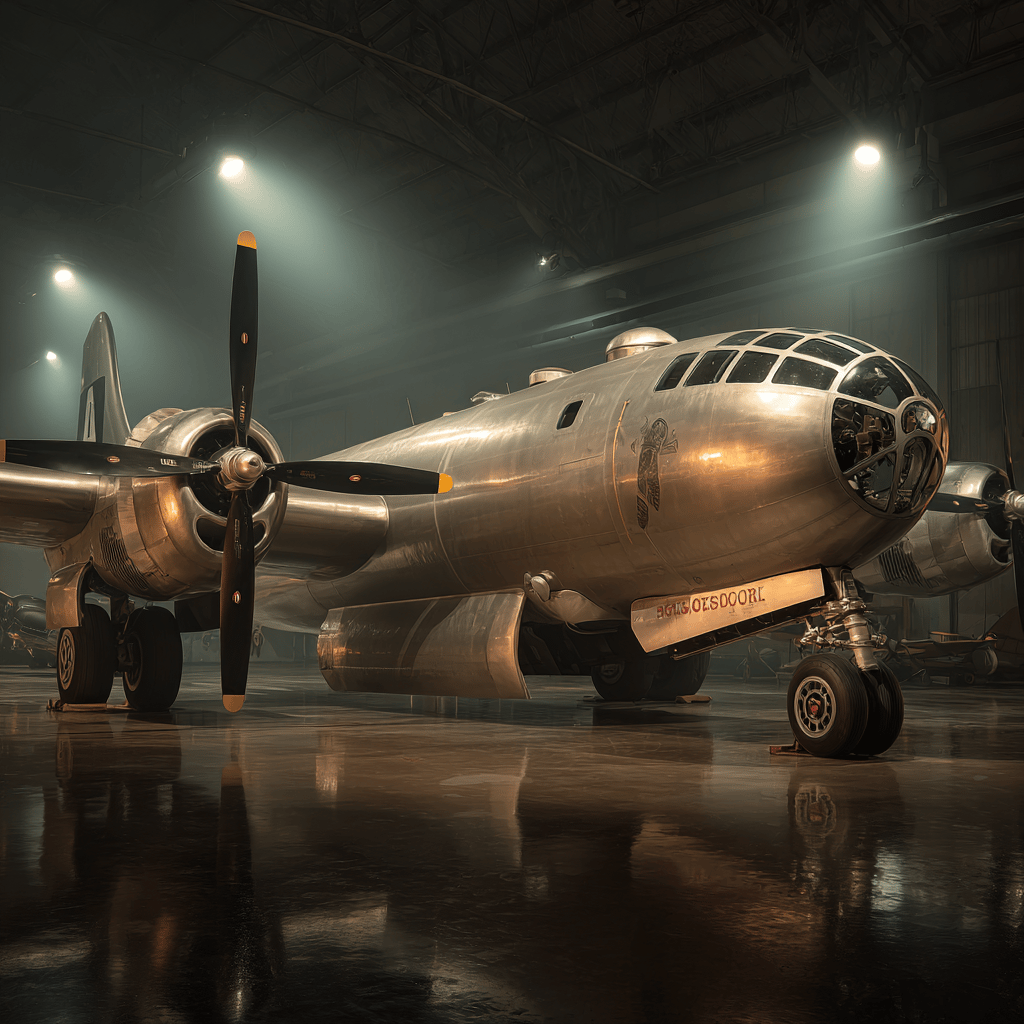

Among the many preserved aircraft held within the extensive collection of the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio—a repository that boasts roughly 350 historically significant planes and missiles—there is one bomber that inevitably captures the profound attention of its visitors. This aircraft, a Boeing B-29 Superfortress affectionately designated *Bockscar*, occupies a prominent place within the museum’s World War II Gallery, not simply due to its technical design or impressive size, but rather because of its singular and world-changing mission. On August 9, 1945, Bockscar released the atomic weapon known as “Fat Man” over the city of Nagasaki, an act that directly precipitated the surrender of Japan and unequivocally marked the conclusion of the Second World War.

The experience of encountering Bockscar in person is enhanced by the presence of knowledgeable museum volunteers. When accompanied by one of these guides, visitors can literally stand beneath the enormous undercarriage of the bomber and view the location from which the 10,000‑pound atomic device was carefully loaded prior to its historic mission. This perspective provides a tangible reminder of the technological precision and immense destructive force that characterized the weapon, and it allows the observer to grasp the scale of the event in a far more visceral way than mere reading ever could.

To appreciate its significance fully, it is necessary to recall the chronological sequence of events that unfolded in August 1945. Just three days after the Enola Gay, another B-29, dropped the “Little Boy” atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima, Bockscar departed on its mission to Nagasaki carrying the second, more powerful plutonium-based device. Upon detonation, “Fat Man” initially killed an estimated 40,000 people instantly and left approximately 60,000 more wounded, according to historical estimates provided by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of History and Heritage Resources. Known thereafter as “the aircraft that ended World War II,” Bockscar served as the harbinger of a new and terrifying age, one defined by nuclear capability and the shifting balance of international power.

Although the atomic strikes were the culminating shock that induced Japan’s surrender on August 15, 1945, they did not act in isolation. Other decisive factors, including the Soviet Union’s simultaneous invasion of Manchuria and the already exhausted state of Japan’s military infrastructure, helped to compel the Japanese emperor to announce capitulation. Nonetheless, the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were understood internationally as unprecedented acts that decisively hastened the end of hostilities.

Preserved in perpetuity, Bockscar was transferred in 1961 to the National Museum of the United States Air Force, where it remains an enduring artifact. Measuring an imposing 99 feet in length and boasting a wingspan that extends more than 141 feet, the aircraft is a striking presence within the gallery. Constructed in 1945 at a cost of $639,000—equivalent to roughly $11.6 million in today’s value when adjusted for inflation—the bomber reflects both the extraordinary financial investment and the advanced engineering ingenuity characteristic of wartime America. The museum’s restoration initiative carefully reinstated the plane’s original nose art, which depicted a stylized boxcar with wings positioned beside a mushroom cloud, along with visual references to its Utah origins.

Its operational history adds further depth to its legend. Bockscar was initially based at Wendover Field in Utah, where its crews trained for the highly secret missions of the 509th Composite Group. In preparation for its critical assignment, its identifying tail markings were deliberately altered to represent the 44th Bomb Group, thereby concealing its true purpose in an elaborate effort of deception. The aircraft was officially named after its regular pilot, Capt. Frederick C. Bock, although circumstances of the day determined that he did not fly it on the Nagasaki mission. Instead, Maj. Charles Sweeney, commander of the 393rd Bomb Squadron—who had previously piloted *The Great Artiste* as an observation aircraft on the Hiroshima strike—took the controls of Bockscar under orders, while Capt. Bock flew *The Great Artiste* in a supporting role over Nagasaki.

During my own visit to the museum in August, I was guided underneath the colossal bomber and shown the very bomb bay in which “Fat Man” had been secured. The museum also houses a faithful reproduction of the weapon itself. This replica, created by refurbishing a demilitarized Mk III bomb casing, has been painted in the exact yellow shade originally chosen to increase its visibility after release. Displayed alongside Bockscar, it conveys the enormity of what a 10,000‑pound weapon containing destructive force equal to 20,000 tons of TNT represented.

Accompanying the artifact is further visual evidence of the strike’s consequences. On display is the remarkable colorized photograph captured by Lt. Charles Levy aboard *The Great Artiste*, which reveals the towering mushroom cloud produced by the detonation. Ascending more than 60,000 feet into the sky, this image embodies both the raw power unleashed and the haunting devastation that followed.

The precise number of casualties from the two bombings is still debated and will likely never be definitively established. Official U.S. military reports in the 1940s suggested approximately 70,000 deaths in Hiroshima and 40,000 in Nagasaki, totaling 110,000. By contrast, later assessments in the 1970s—particularly from Japanese officials and anti-nuclear advocates—suggested far higher numbers: 140,000 in Hiroshima and 70,000 in Nagasaki, for a combined total approximating 210,000. The variance in figures underscores not only the difficulties of historical accounting in the aftermath of unprecedented destruction but also the profound and lasting human cost of nuclear warfare.

Ultimately, Bockscar serves as more than just a relic of aviation history. It embodies the culmination of wartime innovation, the grave responsibilities of strategic decision-making, and the stark reminders of mankind’s capacity for devastation. Standing beneath its massive frame in the museum today, one cannot avoid confronting the sobering lessons it continues to impart.

Sourse: https://www.businessinsider.com/wwii-planes-atomic-bomb-b-29-bockscar-2025-9