This first-person narrative emerges from a conversation with Scott Kern and has been carefully edited for both clarity and conciseness. It recounts his unique experience living in deliberate isolation over the course of the summer months, specifically from June until September, when his daily rhythm aligns not with artificial schedules or electronic reminders, but with the elemental forces of tide and sun. Sunset signals a time to pause for nourishment and rest, while the shifting tide—when it drops low enough to brush against the base of his mooring buoy—serves as his marker to resume labor on a rock wall designed to counteract the gradual yet relentless process of coastal erosion.

Throughout these warm months, Scott’s constant companion is his dog, who loyally lounges on the beach and roams the shoreline by his side. To Scott, this seasonal environment is more than an island; he calls it “Planet Sand,” a name that reflects both affection and imagination. Officially, it is known as Sand Island, a modest 1.5-acre parcel within Maine’s Casco Bay, located about a quarter-hour boat ride from the city of Portland. Yet unlike other islands that offer modern conveniences, this stretch of land has no utilities—no plumbing, no electrical grid, and not even reliable internet connectivity. Despite these limitations, or perhaps because of them, it becomes his home for three full months each year.

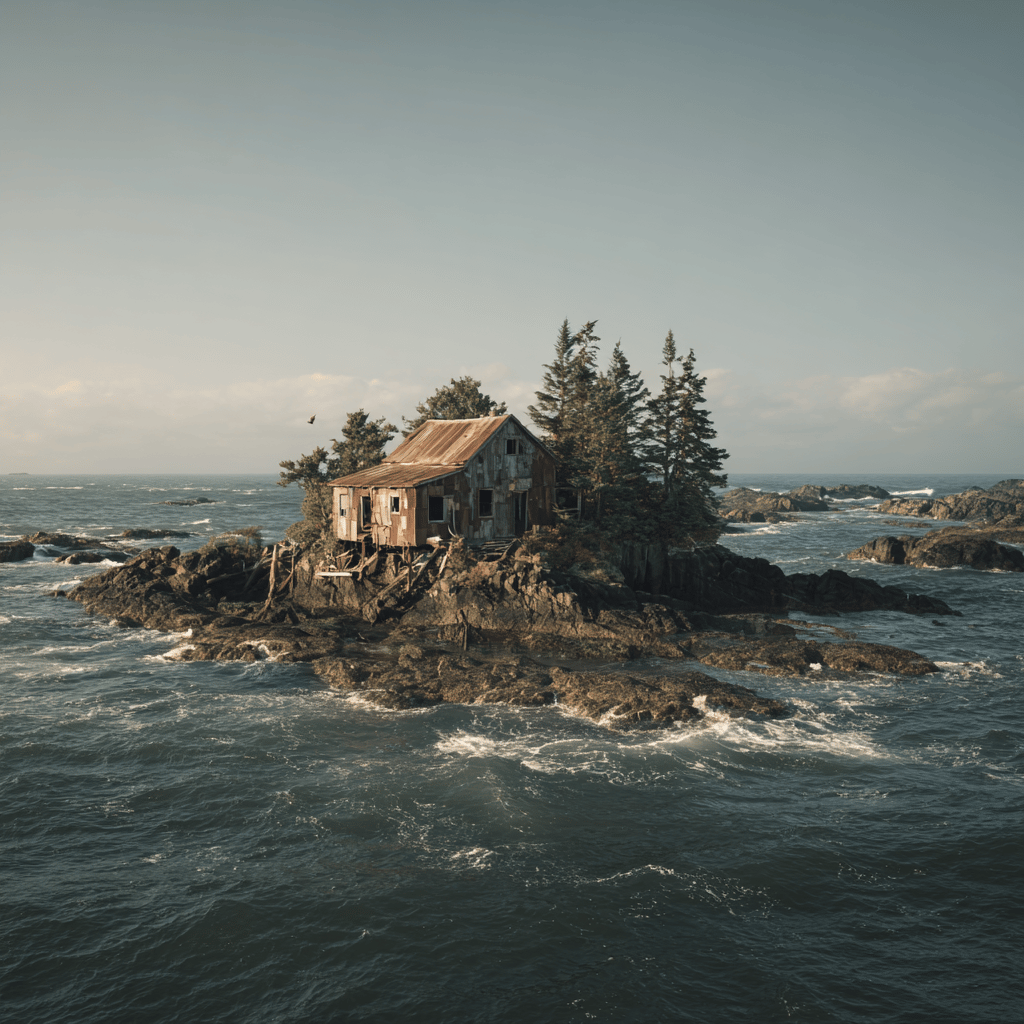

Survival here depends on ingenuity. His living quarters—a structure fondly referred to as the Garden Shed Tree Fort—was constructed entirely from discarded construction materials salvaged from mainland dumps. Its dimensions might be difficult to quantify in conventional measurements, but in the vocabulary of Planet Sand, the appropriate term is simply “perfect.” To supplement life’s necessities, Scott operates a gas-powered generator primarily to run a deep freezer, ensuring a reliable supply of food, since he does not fish and finds the taste of seafood unappealing. Instead, his meals favor grilled poultry or beef, though he dreams of expanding his cooking options by adding a slow cooker should he manage to devise a power solution for it.

Venturing into nearby Portland, the closest hub of civilization, requires effort and is avoided whenever possible. His modest boat, limited in speed, transforms what is geographically a short distance into an exhausting 45-minute trip. At times, Scott manages to remain on the island for nearly two months without returning to town, but in general, he resupplies every three to five weeks. Fresh water is procured from a café on another nearby island, where he loads more than 30 gallons at a time before hauling it back across the bay.

Inevitably, curious onlookers ask practical yet mildly intrusive questions about his bathroom arrangements, to which he responds with humor and a firm dismissal: “Next question.” In his view, focusing on such details misses the larger significance of his project. In his own words, existence on Planet Sand embodies something extraordinary—it is part personal journey, part environmental mission aimed at preservation. To divert attention to trivial matters, he feels, is to overlook his effort to shape meaning and contribute, however modestly, to a cause greater than himself.

Scott’s ties to Sand Island stretch back decades to when his parents purchased a half-stake in the property during the 1990s. The family originally resided on another island in Casco Bay, one linked to the mainland by a bridge and supported with paved roads and a close-knit residential community. By contrast, Sand Island was barren and inhospitable: a sandy outcrop choked with poison ivy, devoid of human architecture or any welcoming dock. Circumnavigating its small shoreline requires only 15 minutes, even allowing for navigation across rocky patches. Yet Scott saw potential where others perceived desolation, gradually transforming debris and castoffs into functional tools and shelter—a process of converting waste into value.

His parents, sailors with a 30-foot boat, delighted in visiting Planet Sand, and Scott himself grew increasingly drawn to camping there. Each visit extended little by little, until weekend stays blurred into longer retreats. While in society at large he often felt like an outsider, adrift and disconnected, here on this fragment of land he experienced a profound sense of belonging. The island seemed to call out to him as if it offered both refuge and purpose.

Nevertheless, for many years, he could not fully answer that call. Health struggles combined with substance dependency—including both alcohol and harder drugs—diverted him from the island and eroded his time and energy. In those darker periods, the retreat sat neglected. It was only after embarking on the long and arduous path toward personal recovery that his summers there became once again not just possible, but essential. Returning initially while still drinking, he recalls waking at midday with throbbing headaches, contrasted against visiting day-trippers who arrived fresh-faced, laughing, and savoring family time on the beach. Witnessing such joy in the very space he had dulled by hangovers filled him with sobering clarity: he realized that in squandering his health, he was also squandering this piece of paradise. That recognition spurred his decision to quit drinking, a choice that has endured. This November will mark seven years of sober living, an achievement he credits in no small measure to the grounding stability offered by his summers on Planet Sand.

Although idyllic in photographs, daily life on the island is far from leisurely escapism. Scott dedicates his days to physically demanding projects, whether constructing protective rock walls against erosion or maintaining the winch system necessary for his boat. He documents these undertakings on a YouTube channel, sharing both process and progress with a broader audience. Work is often accompanied by music broadcast from a small battery-powered radio, with his preferred soundtrack composed of upbeat songs from past eras—particularly nostalgic tunes from the mid-twentieth century and the energetic anthems of the 1990s—because their cheerful simplicity seems to align perfectly with his efforts.

While solitude defines much of his routine, he does not live in absolute isolation. Passing boaters occasionally stop by, and every so often the island becomes animated with bustling activity; on one notable day, as many as sixty visitors came ashore at once. Scott delights in these moments, as families wander the beaches, children scramble across rocks, and friends share laughter under the open sky, crafting memories that, in all likelihood, will never fade.

The psychological benefits are undeniable. Research suggests that even 15 minutes immersed in nature can meaningfully improve mental well-being. For Scott, three entire months surrounded by unfiltered landscapes act not only as retreat but as therapy. He describes the island as both mystical and restorative, “magic and medicine” for body and mind alike. Planet Sand, in that sense, is not merely where he lives each summer—it is the crucible that has shaped his sobriety, his resilience, and his renewed appreciation for both simplicity and survival.

Sourse: https://www.businessinsider.com/sand-island-scott-kern-maine-summer-life-2025-9