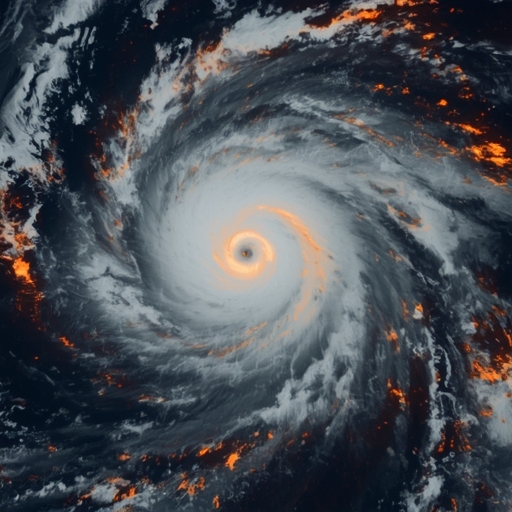

Milton. Haiyan. Patricia. Each of these names evokes vivid recollections of extraordinary tropical cyclones—enormously powerful storms that not only devastated landscapes and communities but also reignited scientific and public debates about whether the existing hurricane classification system can still adequately describe the most extreme events. The question at the heart of this discussion is provocative yet pressing: do we now require the addition of a “Category 6” to our hurricane scale to capture a new class of superstorms whose unprecedented intensity appears to be escalating alongside global warming? A growing number of experts argue in the affirmative, emphasizing that their most recent findings suggest a disturbing trend—these particularly ferocious storms are posing ever-greater risks to heavily populated coastal regions, where millions of people live, work, and depend on fragile infrastructure.

At the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) recently held in New Orleans, I-I Lin—Chair Professor in the Department of Atmospheric Science at National Taiwan University—presented the results of her team’s latest study. Although the paper has yet to undergo peer-review, the preliminary findings are deeply revealing. Lin and her colleagues have identified zones of abnormally warm seawater—described as regional “hotspots”—across both the North Atlantic and the western Pacific Oceans. These regions, where ocean surface and subsurface temperatures reach persistently high levels, act as natural incubators for the birth and intensification of mega-hurricanes. What has alarmed the researchers most is the rapid expansion of these hotspots. The data show that their size and extent have been growing swiftly, which could set the stage for more frequent development of storms surpassing all previous benchmarks of destructive force.

According to Lin, this expanding thermal environment strengthens the rationale for adding a formal Category 6 to the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale (SSHWS). Implementing such a classification, she argues, could significantly improve public understanding and city-level preparedness for extremely high-intensity hurricanes—especially in urban coastal zones where these storms are beginning to appear with troubling regularity. “We truly believe,” Lin stated in an AGU press release, “that the public deserves clearer, more precise information regarding the potential severity of these events.” Her appeal underscores not only a scientific challenge but also a communication and policy imperative: communities need finer distinctions within the hurricane alert system to better anticipate and respond to escalating meteorological hazards.

The justification for a Category 6 becomes especially tangible when recalling Typhoon Haiyan, which struck the Philippines in 2013. It remains one of the deadliest and most violent tropical cyclones ever recorded, claiming at least 6,300 lives and displacing millions more. Under Lin’s leadership, a subsequent scientific analysis attributed much of Haiyan’s unprecedented explosive intensification to unusually warm subsurface ocean temperatures in the western tropical Pacific. The storm’s maximum sustained winds reached about 195 miles per hour (315 kilometers per hour)—a velocity far exceeding the current upper Category 5 threshold of 157 mph (252 kph). Despite being officially labeled as Category 5, Haiyan’s power clearly surpassed what that category was originally meant to describe. Recognizing this mismatch, Lin’s team proposed that storms with sustained winds exceeding approximately 184 mph (296 kph) merit designation as Category 6, to adequately represent their extraordinary strength and hazards. At present, the existing SSHWS framework groups all storms above 157 mph under one broad maximum category, effectively concealing significant gradations in their devastating potential.

Lin’s newer work extends this argument through a careful statistical examination of the world’s strongest cyclones over the past four decades. The study’s long-term analysis reveals a troubling acceleration in the frequency of what could be defined as Category 6-level storms. Between 1982 and 2011, researchers identified eight such extreme cyclones; from 2013 through 2023, that number rose to ten. Remarkably, this means that roughly one-quarter of the recorded Category 6-caliber storms in the last forty years have occurred within the most recent decade—a clear indication of intensifying storm activity within a warming climate system.

The spatial distribution of these powerful storms further reinforces the role of oceanic hotspots. The largest and most active of these thermal breeding grounds currently lies in the western Pacific, to the east of the Philippines and the island of Borneo. Another major hotspot has emerged in the North Atlantic, centered east of Cuba, Hispaniola, and Florida. Moreover, the study concludes that these hotspots are not static; they are expanding and extending into new marine territories. For instance, the North Atlantic hotspot has stretched eastward beyond the northern coast of South America and westward into the Gulf of Mexico—a remarkable expansion that amplifies the threat to the Caribbean and the coastal United States. Lin and colleagues estimate that anthropogenic, or human-caused, global warming accounts for approximately sixty to seventy percent of this growth. This warming influence, they argue, correlates directly with an increased likelihood of forming ultra-intense Category 6 hurricanes.

As the planet continues to heat at an accelerating pace, the implications of these findings are impossible to ignore. Humanity may be entering an era in which tropical storm systems surpass both our physical defenses and our descriptive frameworks. Whether the solution lies in adding a Category 6 to the SSHWS or in developing an entirely new classification scheme, the question remains urgent. What this emerging body of evidence makes abundantly clear is that the risk landscape is evolving rapidly, and communicating that reality transparently to the public is essential. The world now faces not only the meteorological challenge of understanding how such storms form but also the moral responsibility to act—through climate policy, adaptation, and preparedness—to mitigate the devastating potential of these next-generation mega-hurricanes.

Sourse: https://gizmodo.com/hotspots-capable-of-driving-catastrophic-mega-hurricanes-are-spreading-across-the-oceans-2000702025