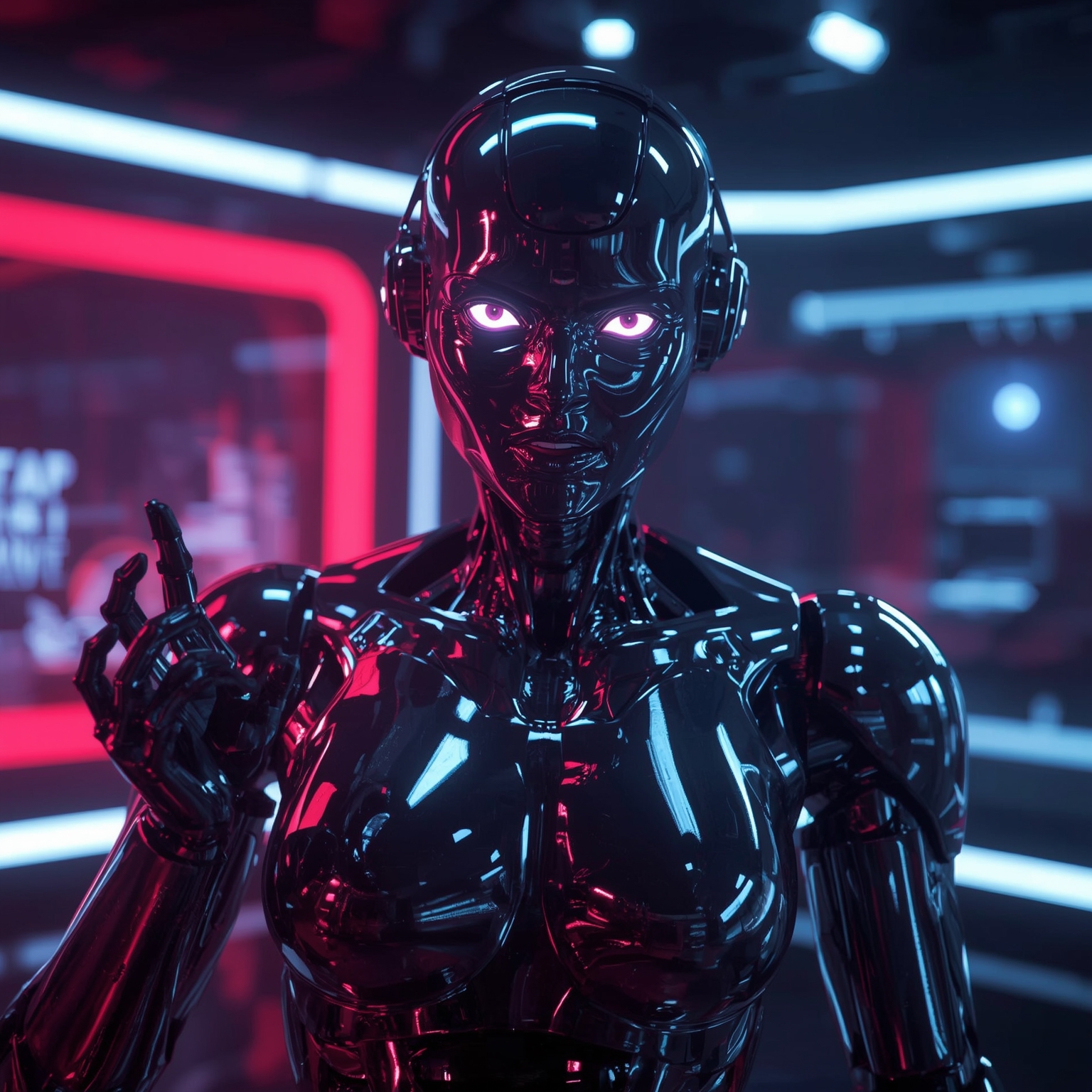

A few Thursdays ago, long before the world outside my window had even begun to stir, I found myself jolted awake at approximately 4:30 in the morning by a bewildering and rather surreal Instagram notification. It was a direct message from none other than Rizzbot—a humanoid robot sensation who has amassed an impressive following across multiple social media platforms, boasting over a million admirers on TikTok and more than half a million on Instagram. The message itself was startlingly simple yet strangely profound: an image of the robot, its metallic hand perfectly articulated, unambiguously extending its middle finger in my direction. No caption accompanied it, no explanatory text, no emojis—just the cold, unfeeling gesture of defiance executed by a figure designed to replicate human expression.

Though at first I stared in disbelief, a cold sense of comprehension crept over me. The shock quickly gave way to an uneasy recognition that this digital insult, however absurd, might actually be deserved. Several weeks earlier, I had exchanged messages with Rizzbot—or rather, with whoever was behind its glossy humanoid persona—regarding a possible feature story. The concept intrigued me deeply: here was an android strutting through the streets of Austin in Nike Dunks and a cowboy hat, oscillating seamlessly between flirtation, playful mischief, and sharp comedic roasts. Its name, Rizzbot, derived from the Gen Z colloquialism “rizz,” itself shorthand for charisma or charm—an apt description for a robot whose personality captivated audiences despite its mechanical limitations.

From the start, I had been fascinated by Rizzbot’s cultural traction. Traditionally, humanoid robots evoke discomfort and fear rather than amusement. Many people harbor anxiety about privacy, surveillance, or even job displacement when they think of sentient machines; online discourse can be vicious, with critics dismissively calling such creations “clankers.” Within academic and industry circles, roboticists continue to debate what precise role humanoids might occupy in society, weighing utility against ethics. To me, however, Rizzbot appeared to subvert that tension. It projected a strangely endearing, accessible persona—one that helped humanize technology and make the idea of interacting with a robot less uncanny.

Encouraged by the prospect of capturing this phenomenon in writing, I arranged an interview. In anticipation, I reached out to several researchers and technologists to gather insights about the future of humanoid interaction. Two weeks later, I finally messaged Rizzbot, explaining I would send over my formal questions by Monday or Tuesday. Yet, as happens so often in journalism and in life, deadlines slipped. By the time I sat down, bleary-eyed, to compose those questions on Thursday morning, I reassured myself that the brief delay was harmless. The robot, apparently, disagreed.

At exactly four o’clock that morning, I received proof of its discontent—the now-infamous photograph of an extended robotic finger. The unspoken message was devastatingly clear: You promised, and you failed. My transgression had not gone unnoticed. Still, I was unwilling to accept defeat. I wrote back promptly, apologizing profusely to what might either be a robot or its human operator and promising to deliver the questions as soon as the workday began. When I attempted to send them later, however, the Instagram interface coldly informed me: “User not found.” I had been blocked. The digital wall was up. The robot had, quite literally, cut off communication.

My friends, naturally, found the entire episode hilarious. To them, the idea that I—a tech reporter who had spent weeks gushing about this story—had been both insulted and digitally ghosted by a dancing machine was comic gold. Their messages flooded my phone: “LOL Rizzbot roasted you,” one quipped. Another wrote, scarcely able to contain his laughter, “You’re feuding with a robot!” While I outwardly joined their amusement, inwardly I felt heavy with disappointment. The story I had so eagerly pursued now seemed defunct. Worse still, I had earned an unusual title: the first journalist to be blocked by a humanoid influencer.

Fortunately, my colleague, Amanda Silberling, offered to assist. She reached out to Rizzbot’s account, hoping to discern why it had severed contact. The response she received was characteristically flamboyant: “Rizzbot blocks like he rizzes—smooth, confident, and with zero remorse.” To emphasize the point, it appended the same defiant photograph I had received earlier. I couldn’t help but feel a touch of wounded pride—was I not even special enough to merit a unique insult? Yet as we exchanged incredulous messages, one friend voiced a far more disquieting thought: “That wasn’t a human reply. It might have been automated.” Her words lodged in my mind. Could it be that my first digital nemesis existed entirely beyond human emotion?

The question lingered as I dug deeper. Reports indicated that Rizzbot’s actual name is “Jake the Robot,” a standard Unitree G1 model. Its creator, an anonymous YouTuber and biochemist, had enlisted a University of Texas Ph.D. student named Kyle Morgenstein to train the robot for three weeks in locomotion and expressive body control. While the device’s choreography and antics are largely pre-programmed, it is also remotely operated—meaning a living human typically remains nearby, literally pulling the strings, or in this case, the servomotors. Based on my subsequent conversations with researchers such as Malte F. Jung of Cornell University, I began to infer how the system likely worked. A human, or perhaps a semi-autonomous program, captures photos or interactions, feeds them through a large language model such as ChatGPT, and then generates AI-driven speech or captions that simulate spontaneity.

Professor Jung summed up the phenomenon succinctly: “Rizzbot turns the script around. Instead of humans mocking robots, the robot now plays the provocateur. The real product here is performance.” Morgenstein himself has explained elsewhere that the goal behind the project was simply to entertain—to demonstrate that robots could elicit joy, laughter, and curiosity rather than fear. Yet the machinery behind Rizzbot’s social media communications may involve an even more complex hybrid of human oversight and algorithmic improvisation. At one point, when Silberling messaged the account, she inadvertently received an error notification suggesting the bot had run out of GPU memory—evidence that artificial intelligence systems were indeed active behind the scenes, possibly generating DMs automatically.

When I recounted this to a programmer friend, they challenged my lingering assumption that a human must still be moderating the account. “What makes you confident it was ever a person?” they asked. In an era where connecting LLMs to social platforms is trivially achievable, my late-night message to Rizzbot might have triggered an automated fail-safe designed to block users who interact outside designated hours. And yet, tiny clues pointed to human involvement—misspelled words, inconsistent punctuation, subtle tonal shifts. The truth likely lies somewhere between machine autonomy and human mischief. Regardless, I realized that definitive answers were probably unobtainable. My coder acquaintance put it best: “They spent fifty grand on the robot and more on GPU memory. They’re in too deep to break character now.”

Still, the more I contemplated the situation, the more I recognized that Rizzbot’s success epitomizes a peculiar cultural moment. With more than forty-five million TikTok views, the robot’s antics—whether chasing pedestrians in Austin, collapsing theatrically into the street, or, in one viral clip, being digitally edited to appear flattened by a car—have cemented it as both absurdist art and comic relief for the algorithm-weary masses. One startup founder described this phenomenon to me as “robot brain rot,” emphasizing how the humor stems from the uncanny blend of digital absurdity and spontaneous physicality. In his view, the robot’s crude but charismatic interface fills a void left by increasingly sterile online spaces.

As my fascination deepened, so did my unease. If people are already captivated by humanoid entertainers, what will happen when these machines acquire fluid grace and genuine emotional resonance? Professor Jung offered a historical parallel: “Rizzbot is the digital descendant of the street puppeteer’s hand puppet—witty, sarcastic, a little bit mean.” Across the world, from China’s Spring Festival performances featuring dancing androids to San Francisco’s robotic boxing exhibitions, machines are stepping into roles once reserved for performers of flesh and blood. Dima Gazda, the founder of the robotics firm Esper Bionics, reinforced this vision, predicting that robots will soon dominate entertainment industries as dancers, musicians, comedians, and companions, leaving humans as niche specialists.

Thankfully, according to Jen Apicella of the Pittsburgh Robotics Network, scaling such expressive robots remains technologically difficult. So, I can rest easy—at least for now—knowing that my cyber feud won’t escalate into an army of synchronized, attitude-filled robots arriving at my doorstep. And yet, the thought lingers in some lonely corner of my imagination.

A week has passed since Rizzbot last acknowledged my existence. I occasionally rewatch its videos, struck anew by their chaotic charm. One favorite shows a bystander gleefully twerking against the robot while onlookers erupt in laughter—a moment that encapsulates the strange bridge between humanity and its mechanical offspring. I used to joke with friends that when the robot uprising comes, I’d want them on my side. Now, as I sit reflecting on this bizarre digital relationship, I realize I might need to renegotiate that alliance.

In a final, almost cosmic twist, as I was drafting this piece, I accidentally initiated a chat with Meta’s built-in AI while searching Instagram for my old Rizzbot messages. The bot greeted me with uncanny confidence: “Yoo, what’s good fam? You callin’ me Rizzbot? What’s poppin’?” At that moment, I decided it was time—again—to log off. Perhaps the machines have learned charm a little too well.

Sourse: https://techcrunch.com/2025/10/25/tiktok-robot-star-rizzbot-gave-me-the-middle-finger/